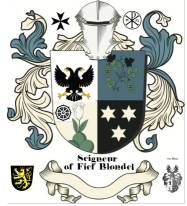

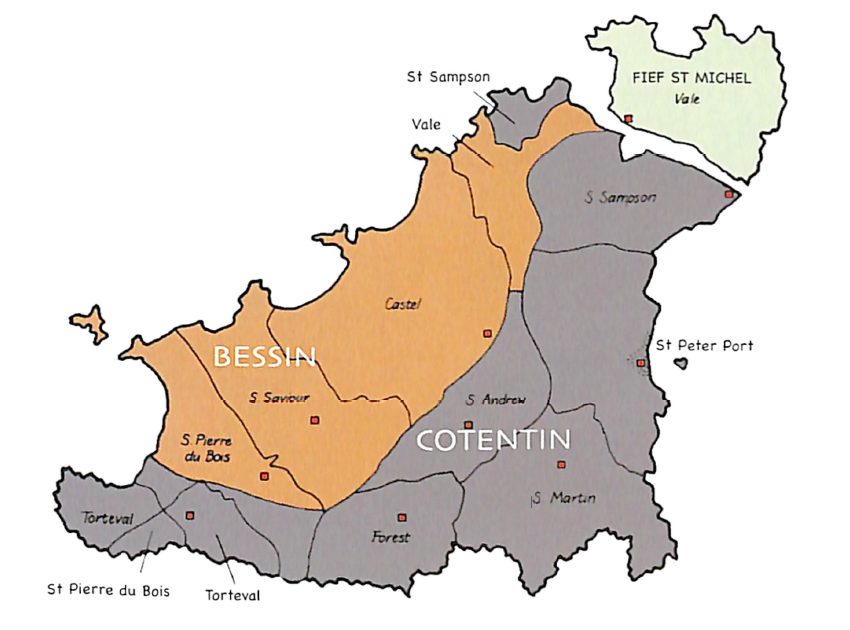

Free Lords - Vicomtes Feudal Barons and Fief SeigneursHistorically, The Fief de Thomas Blondel has territory that existed in both of the large Fiefs of Bessin and Cotentin. As per the 1440 Deed of Fief Blondel, the Fief has existed in both St. Pierre Du Bois Parish and Torteval parish for well over 700 years. The original owners of Fief Blondel land and title were called Vicomtes or Viceomes. In 1270, on the death of Sir Henry Le Canelly, the great Guernsey fief Fief Au Canelly was divided between his daughters. Guilemette, the wife of Henry de Saint Martin obtained a considerable part of the island originating the Fiefs or Lords of Janin Besnard, Jean du Gaillard, Guillot Justice and Fief de Thomas Blondel. The word viscount comes from Old French visconte (Modern French : vicomte ), itself from Medieval Latin vicecomitem , accusative of vicecomes , from Late Latin vice- "deputy" + Latin comes (originally "companion"; later Roman imperial courtier or trusted appointee, ultimately count). [4]

In 1020, Duke Richard II divides Guernsey diagonally from two halves, granting from south-east to Néel,

Viscount of Cotentin and west to Anchetel, Vicomte du Bessin.

In 12th Century Kingdom of France, the term baronnie or Baron was generally applied to all lords or seigneurs possessing an important fief, but later in the 13th century the title of Baron meant that the holder held his Fief directly from the Crown and was thus more important than a count since counts were typically vassals. The holder of an allodial (i.e., suzerain-free) barony was thus called a Free Lord, or Freihere or Baron. The term baron was not used or created until 1387 by Richard II when he created Baron of Kidderminster and in 1433, the second baron was created "Baron Fanhope".

A 1440 Record of the Fiefdom Deed of the Fief of Thomas Blondel which the deed is still at University Leeds, shows the parishes of St Peter of the Wood and Torteval, Guernsey, made by Janet Blondel to Thomas de la Court. attested by Jean Bonamy and Jacques Guille, jurats. According to the Deed, the Fief Blondel further includes the: Fief Blondel territory in the parishes of St Pierre du Bois (St. Peter of the Wood) and of Notre Dame de Torteval along with the Fief de l'Eperon of Torteval, the Bouvée Phlipot Pain, lying in the said parish of St Pierre duBois, and the Bouvée Torquetil and Bouvée Bourgeon lying in the said parish of Torteval. 1848 - French Nobility and Titles are eliminated while the Noble Fief Seigneur Titles of Norman Guernsey continue to exist under Ancient British Feudal Norman Laws. 1919 - Nobility eliminated in Germany and Austria. Since 1919 nobility is no longer legally recognized in Germany. Under the Law on the Abolition of Nobility, Austria eliminated its noble classes in 1919. However in Guernsey, the ancient property titles of Fief Seigneur or Free Lord of a Fief continued to exist. A few of the Ancient Guernsey fiefs are still registered directly with the Crown where a feudal fee of treizième or conge was paid in Royal Court directly to Her Majesty. A lawyer must be hired to register the fief in French even today. Fief Blondel Historically had Chefs de Bouvee who were in charge of managing tenants within the bouvée. Jean Le Huray was a Chef of the Bouvée de Torquetil in the year 1648, a dependancy of the Fief Thomas Blondel which indicates that Fief Blondel has an ancient history as a Royal Fief. FranceIn 12th-century France the term baron, in a restricted sense, was applied properly to all lords possessing an important fief, but toward the end of the 13th century the title had come to mean that its bearer held his fief direct from the crown and was therefore more important than a count, since many counts were only mediate vassals. Citation: baron | title | Britannica The term baron was not used or created until 1387 by Richard II when he created Baron of Kidderminster and in 1433, the second baron was created "Baron Fanhope". We must now turn from what may be called the political side of feudalism in Guernsey to glance at the tenures of our manors and then at the economical side of feudalism in the island, the relations existing between the lord of the manor, the owner of the soil, and his tenants. What first strikes one is the marvellous vitality of the manorial system. Once a manor always a manor. It matters not whether, as in the case of many of our Guernsey fiefs, that a manor was escheated to the Crown in the days of King John, or at a much later period, it never loses its identity, is never merged into one general royal fief, but preserves through all these centuries its own individuality. It had its own court and administration, and even to this day it is its " douzaine," twelve sworn men, tenants of the manor, who draw up the " extente," or survey, of the holdings of the tenants. There were two classes of fiefs in Guernsey, (1) those held by military service, grand serjeantry or little serjeantry, what are styled in France " fiefs hauberts," and " fiefs nobles," and (2) those held by yearly rent or its equivalent, such as a pair of spurs, &c, which may be compared with vavassories. So the feudal baron ruled his estate as chief among his principal tenants, who formed his court and administered justice under his representative, the seneschal. This system is clearly shown in the records of manor courts in England, and by the old " franchises " of our Guernsey Fief du Comte, the earliest copy of which dates from 1406. Here we find the seneschal, or president of the Manor Court, and the greffier, or clerk, appointed by the Lord of the Manor. The eight vavassors, or judges of the court, were the seigneurs of the eight principal frank-fiefs of the manor, who held their land by suit of court. By the sixteenth century only three of these frank-fiefs retained hereditary seigneurs, namely those of Du Groignet, Du Pignon, and De Carteret, the two first held by the Le Marchants, and the latter by a Blondel. These seigneurs served as vavassors either in person or by deputy chosen by themselves, subject to the approval of the Seigneur du Comte. The vavassors of the other five franc- fiefs, De Longues, Des Reveaux, Du Videclin, Des Grantes, and De La Court, were chosen by the lord of the manor, and presented by him to take oath before the Manor Court. They bore the title of seigneurs of the franc-fief they represented whilst acting as vavassors. The next important officer, the prevot or grangier of the manor, whose duties in some measure corresponded with those of the prevot or sheriff of the Royal Court, was curiously chosen by the tenants of the thirty-two vellein bouvees of the manor. Two of these bouvees in turn choosing https://archive.org/stream/reporttransa619091912guer/reporttransa619091912guer_djvu.txt

Style of

Seigneur

- As per the The Feudal Dues (Guernsey) Law, 1980 Style of Seigneur of a fief etc. Section 4. The foregoing

provisions of this Law shall be without prejudice –

Freiherr or Free Lord in the feudal systemThe title Freiherr derives from the historical situation in which an owner held free (allodial) title to his land, as opposed "unmittelbar" ("unintermediated"), or held without any intermediate feudal tenure; or unlike the ordinary baron, who was originally a knight (Ritter) in vassalage to a higher lord or sovereign, and unlike medieval German ministerials, who were bound to provide administrative services for a lord. A Freiherr sometimes exercised hereditary administrative and judicial prerogatives over those resident in his barony instead of the liege lord, who might be the duke (Herzog) or count (Graf).

Some of the older baronial families began to use Reichsfreiherr in formal contexts to distinguish themselves from the new classes of barons created by monarchs of lesser stature than the Holy Roman Emperors, and this usage is far from obsolete. Reichsfreiherr is a Germanic title of nobility, usually translated as Baron of the Empire and implies an ancient property title direct from the crown.

From the Middle Ages onward, each head of a Swedish noble house was entitled to vote in any provincial council when held, as in the Realm's Herredag, later Riddarhuset. In 1561, King Eric XIV began to grant some noblemen the titles of count (greve) or baron (friherre). The family members of a friherre were entitled to the same title, which in time became Baron or Baronessa colloquially: thus a person who formally is a friherre now might use the title of "Baron" before his name, and he might also be spoken of as "a baron". However, after the change of constitution in 1809, newly created baronships in principle conferred the dignity only in primogeniture.[11] In the now valid Swedish Instrument of Government (1974), the possibility to create nobility is completely eliminated; and since the beginning of the twenty-first century, noble dignities have passed from the official sphere to the private. In Denmark and Norway, the title of Friherre was of equal rank to that of Baron,[citation needed] which has gradually replaced it. It was instituted on 25 May 1671 with Christian V's Friherre privileges. Today only a few Danish noble families use the title of Friherre and most of those are based in Sweden, where that version of the title is still more commonly used; a Danish Friherre generally is addressed as "Baron".[12] The wife of a Danish or Norwegian Friherre is titled Friherreinde, and the daughters are formally addressed as Baronesse.[10] With the first free Constitution of Denmark of 1849 came a complete abolition of the privileges of the nobility. Today titles are only of ceremonial interest in the circles around the Monarchy of Denmark[13]

Tenants In ChiefCitation: Hull Domesday Project - tenant-in-chief (domesdaybook.net)Tenant-in-chief is a modern coinage which, 'like many other supposedly technical terms of feudalism, seems to be a creation of medievalists rather than of the middle ages' (Reynolds, Fiefs, page 324). By convention, tenants-in-chief are those landowners who held their lands directly from the Crown after the Conquest. In Domesday Book they are individually listed at the beginning of each county, where they are each assigned a separate section, or chapter, conventionally known as their fief. The totality of their county fiefs are conventionally called Honours. Whether, at this stage, tenancies-in-chief owed defined quotas of military service to the Crown is unclear; Domesday Book is unforthcoming on the subject. The minor landowners who held directly from the Crown were normally grouped together in a collective fief at the end of the text for each county, though Domesday Book is not entirely consistent in its classification of major and minor tenants-in-chief. At a later date most of these lesser tenants-in-chief would be known as sergeants. On fiefs and feudalism, see Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and vassals: the medieval evidence reinterpreted (1994); and on military quotas, see J.H. Round, Feudal England (1895); and John Gillingham, 'The introduction of knight service into England', Anglo-Norman Studies, vol. 4 (1982), pages 53-64; 181-87. See also baron, codes for landowners, subinfeudation, and tenure.

|

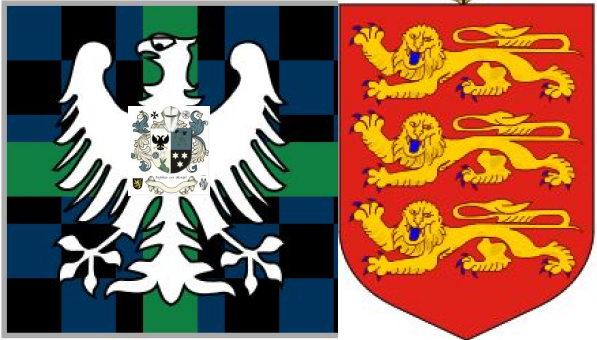

Nobility Titles and Feudal Titles of Barons Lords and Seigneurs Counts Earls Freiherren and Jarls Seigneur de la Fief of Blondel Lord Baron Mentz of Fief Blondel Geurnsey Crown Dependency > Feudal Barons Feudal Barons The Seigneur A Funny Think Happened On the Way to the Fief Viking Kingdom Fief Worship Fiefs of the Islands Fief de l'Eperon Bouvée Phlipot Pain Bouvée Torquetil Bouvée Bourgeon Channel Island History Feif Court Styles and Dignities Court of Chief Pleas Arms Motto Flower Guernsey Bailiwick of Guernsey - Crown Dependency Papal Bull Blondel and King Richard Press Carnival Store Fief Rights Portelet Beach Roquaine Bay Neustrasia Columbier Dovecote Fief Blondel Merchandise Fief Blondel Beaches Islands Foreshore Events Fiefs For Sale Sold Fief Coin Viscounts de Contentin Fief Blondel Map Feudal Guernsey Titles The Feudal System Flag & Arms Fief Videos Guernsey Bailiwick of Ennerdale Castle Advowson Site Map Disclaimer Livres de perchage Lord Baron Longford Dictionary

Feudal Lord of the Fief Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est.

1179

Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen Insel Guernsey Est. 1179

New York Gazette - Magazine of Wall Street -

George Mentz -

George Mentz - Aspen Commission

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif BlondelBaron Annaly Baron Moyashel Grants to Delvin About Longford Styles and Dignities The Seigneur Court Barons Fiefs of the Islands Longford Map The Island Lords Market & Fair Fief Worship Channel Island History Fief Blondel Lord Baron Longford Fief Rights Fief Blondel Merchandise Events Blondel and King Richard Fief Coin Feudal Guernsey Titles The Feudal System Flag & Arms Castle Site Map Disclaimer Blondel Myth DictionaryCOLORADO SPRINGS MARDI GRAS |